Kanji, Mnemonics, Etc

Lately, I’ve been learning kanji “properly”, from scratch. Considering I’m about three and a half years into learning Japanese seriously, this is kind of a funny sentence to say. I should note that, despite having my self-admitted kanji knowledge, for some mysterious reason, I can read more or less anything I want. I mostly read manga, and not anything truly challenging like novels, but I think this is somewhat of a testament to my reading ability.

The way I learned, as far as I can remember, is that I would try to learn vocabulary by reading. Eventually, I learned to recognize words in a sort of gestalt way, and my brain picked up on the general shapes of words (as most brains do, when reading, I think).

Seeing common kanji used in different words also gave me some sort of intuition for meanings and readings, and I can with reasonable accuracy guess the reading of a word based on context. I don’t know exactly what’s going on under the hood, but the brain is built to learn language, and I don’t really care how I learned as much as that I did.

However, I did run into problems. When kanji are displayed on their own, in strange fonts, or in unfamiliar contexts, I would often struggle to read them. Take, for example, the title of the video game Katamari Damacy 塊魂.

These two kanji are very similar looking (lump and soul), but if you, like me, read sentences as a whole, there’s rarely any situations where you could get them confused. But on their own, like when reviewing flashcards, I would mix them up pretty frequently, because I never bothered to look at the radicals on the left. And as my known vocabulary ticked into the 10k - 12k range, I started to encounter more words that had rare kanji for which my usual network of associations would not provide adequate reinforcement. So this time, I decided to buckle down and commit to learning kanji properly and in detail.

I’ve tried to learn kanji “properly” a couple times before, generally via the mnemonics method, which I do think is quite useful:

- At first, I tried to go through an Anki deck for Remembering the Kanji, but I got bored and ultimately felt it was a waste to associate all these Japanese characters with often unrelated English words.

- Next, I tried to come up with my own keywords for kanji in Japanese. For example I would have a flashcard for 物 (thing) and write もの, the most common reading. This sort of worked, but it was tedious to come up with my own keywords for each kanji, and since I was making them up as I went, I had to go back and revise my keywords constantly.

- I also tried to learn how to write kanji a few times, using apps on my phone, hoping that the physical interaction would help them stick. But I also ended up finding this tedious, and would often make repeated mistakes with the stroke order when writing even hiragana and katakana. I felt it wasn’t a good use of my time compared to learning more vocabulary, and went back to that.

So what am I doing now?

I’m going back to Remembering the Kanji, lol. I downloaded some Anki deck with crowdsourced mnemonic stories and just pushed through it. But this time is a bit different. For one, I’m not sentence mining as much these days, so my vocab load is a lot lower and I can focus on these kanji flashcards. But it also helps that I’ve seen most of these kanji dozens of times already, just without paying attention to all the radicals. So I’ll see something like 釣 and recognize the word for 釣る, but now with the additional knowledge that 釣 is “made up” of “golden” and ”ladle” — which is different than 針, a golden needle! I have the vocabulary, and some tenuous connection to the kanji that is anchored in associations, and the mnemonics are working to build up the “kanji fluency” so that I can quickly parse the components and associate them with the words more strongly.

I want to describe this feeling for my future self, because one of the mysterious things about learning a language is that your memory plays tricks on you. It’s difficult to remember what it was like to not know something, after you’ve already learned it. But I’m hoping this will be a real breakthrough for me. Already, I’m starting to tease apart components in rare kanji that I used to just guess at.

This is a lengthy preamble that was I guess necessary to get to the specific thing I was thinking about today: phono-semantic compounds. No one tells you this about kanji (I learned it from a Matt vs Japan video that I can’t find), but it’s interesting even if it ends up being not as useful as I originally thought, for various reasons.

There are generally six types of Han characters (from Chinese). I’m not talking about Nen here. Let’s go through them one by one.

A picture is worth a thousand words

The simplest kinds of characters are simple pictorial representations. There are:

- Pictographs: like 木 for tree, these are abstract and simple depictions of ideas. These tend to be the easiest to remember, but are also fairly common, so you’ll end up learning them without trying anyway.

- Indicatives: like 本 for root. You can imagine this as a tree but with the roots indicated by the line at the bottom. I’m not sure there are that many of these, and in my head they’re basically the same as a pictograph.

Compounding interest

Phonetic-phonetic compounds

These are extremely rare and I’m not even sure any exist in Japanese, because of katakana, which is extremely flexible in representing sounds. The purpose of these compounds were, from my understanding, to represent sounds that didn’t exist in Chinese using a close approximation of combinations of ones that did (for example, this might be necessary to write Vietnamese words). I actually didn’t know these existed until recently.

Compound ideographs

These are already essentially stories built from multiple smaller characters. or example, 武 for military.

On the top, we have a dagger-axe 戈. On the bottom, foot or stop 止. These characters basically already are mnemonics, so it used to bother me that we don’t actually learn those stories with our mnemonics methods. But there’s a couple considerations to note here:

- First, language is of course organic and evolving, so it’s possible that most of these characters originally had a story but that parts were simplified or changed out of convenience, making the story useless.

- Second, who was even writing these stories down? It’s not like they were agreed upon by a central authority. They would have had to spring up out of an entire community as a collectively understood meaning, making the idea of a “canonical” story fraught.

For this example, Wiktionary says:

The graphical origin of 武 as “to stop violence” — the ultimate state of just warfare — is traditionally attributed to King Zhuang of Chu [597 BCE].

Pretty abstract, lol, and to be honest this seems to me like a bit of a “just-so” story. There’s only a few such compounds, so it’s not worth arguing about, but apparently, there’s some debate amongst linguists whether such stories even exist in the first place or whether they are actually just phono-semantic compounds, which we’ll get to later.

Loan Graphs and ateji

Loangraphs are the most interesting to me, and the concepts are relevant to explaining the origins of phono-semantic compounds in Chinese as well as why kanji are the way they are.

Language is spoken first, and written later. Writing was a technology that had to be invented. Characters had to be assigned to words, which was arguably our first mistake as a species. The idea of a loangraph is taking a word and assigning it a character that already represents a word with a similar pronunciation. I won’t be talking about loangraphs specifically, as all the best examples seem to be in Chinese. Instead, I want to talk about a similar concept in Japanese, called (phonetic) ateji. Per Wikipedia:

... the word "sushi" is often written with its ateji "寿司". Though the two characters have the readings 'su' and 'shi' respectively, the character '寿' means "one's natural life span" and '司' means "to administer", neither of which has anything to do with the food.

So we can assume that what happened here was that there was a word sushi floating around in the language, and when it eventually came time to write it down we decided to pick words that hinted at the reading.

But Japanese already has a set of phonetic characters used for spelling out characters from foreign languages, and it’s called katakana. Ateji is thus not very common.

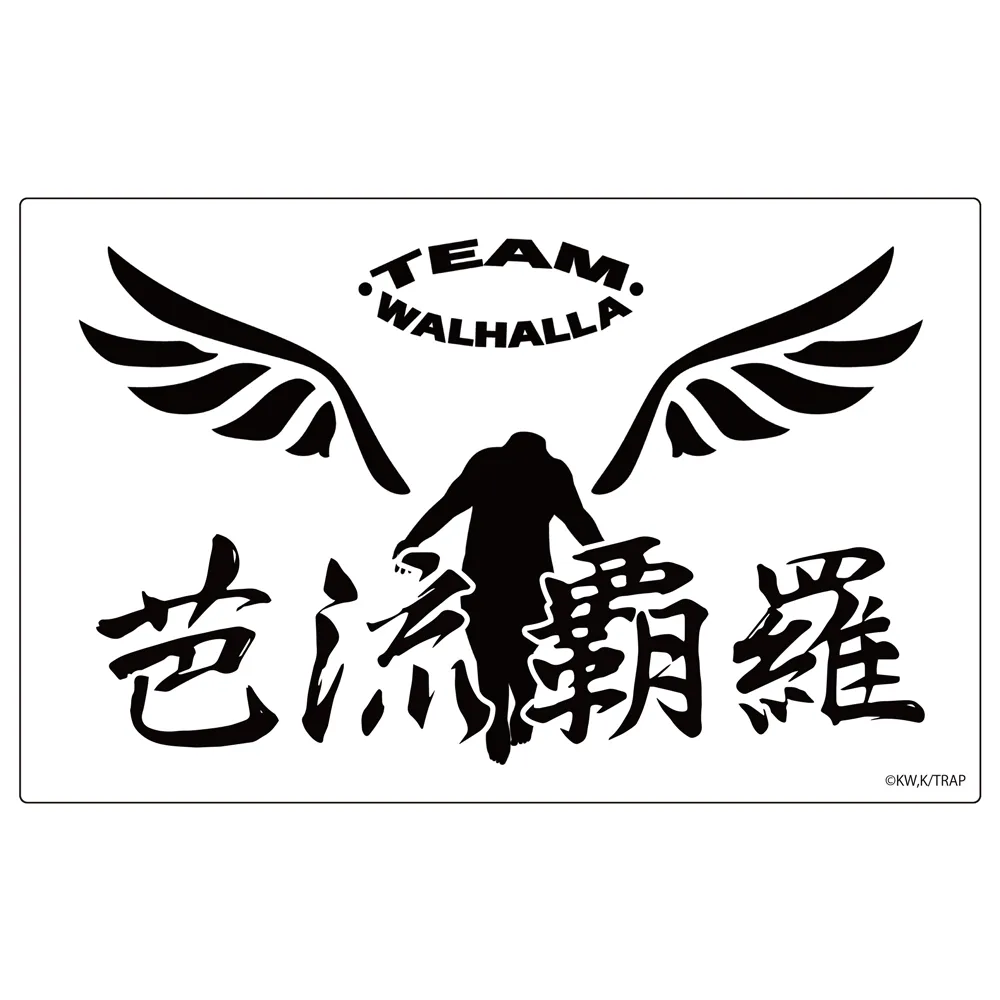

I do still love to think about ateji though, as the instances I’ve seen are often for fun and for wordplay purposes. For example, in the delinquent manga Tokyo Revengers, a lot of the gang names use phonetic ateji to represent words of foreign provenance all while expressing some sort of badass meaning. I think this is a common gang thing, since I’ve seen it in other delinquent manga, but I’m not sure.

My favorite example is 芭流覇羅(バルハラ), read "Valhalla" (Baruhara):

Let's break this down:

- 芭: plantain (ba)

- 流: flow (ryuu). Not quite ru, but close enough.

- 覇: supremacy (ha)

- 羅: spread out (ra)

It's pretty close! Plus, the latter three kanji are pretty cool ones. 羅 in particular evokes 修羅, the god of destruction Asura, or the derived 修羅場, which means a scene of carnage, and I think that's somewhat intentional.

It’s also a common technique in the wordplay-heavy domain of Yugioh cards, or all manner of special attacks in action manga and the like. A more common technique, though is semantic ateji, where the kanji are used for meaning and furigana on top indicates the reading. In One Piece, for example, Sanji has attacks like this one:

The furigana (reading) is concasse, which literally means "to crush" in French, but it's a culinary term meaning "to roughly chop". The kanji read "rough" and "smash", so it gets across the meaning, even though those two kanji together are not a word in Japanese.

Phono-semantic compounds

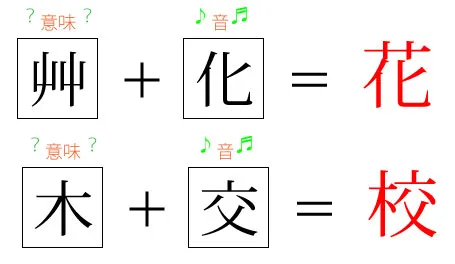

I think, other than a few pictographs, that nearly all kanji are derived from Han characters that were originally phono-semantic compounds. In a typical example, there’s a component (generally on the right or top) that (roughly) represents the pronunciation of a word, in a similar way to loangraphs above. Then, for disambiguation purposes, there’s another compound that represent the meaning of the characters, typically on the left or bottom. Since Chinese is read top to bottom and then right to left, I think of this as saying the reading first and then meaning in parentheses. This process can be repeated several times, as compounds can be nested within other compounds.

When I first found this out, it kind of blew my mind. It helps to contextualize some of the seemingly unpredictable combinations of characters that you see in kanji. In Japanese, phono-semantic compounds are called 形声文字, which is the perfect way to describe it. But there are two reasons why this doesn’t solve all our problems in life forever:

- Remember what I said before about language being organic and evolving. Phonetics can shift over time, and what once made perfect sense as a phono-semantic compound now may just seem confusing as characters lose their original pronunciations.

- Japanese isn’t even Chinese (perhaps this is the main issue we Japanese learners have to face in our daily lives). Japanese is a bit like English, a horrific Frankenstein of a language, but then again, all languages are a bit like that. Before they started using kanji to write these words down, Japanese people already had a whole indigenous language. But also, there are plenty of words in Japanese that are cognates with Chinese, with extremely similar readings. This makes kanji, in theory, extremely hard to read, but in practice of course millions of children have done it and it’s really not that difficult. Often, these readings will be described as kunyomi (from the indigenous Japanese) and onyomi (Chinese origin), and a kanji can take on multiple readings of both types in its everyday life.

I think when it comes to language, it is not a good idea to try to “solve” it like a puzzle, but rather to understand the general principles that explain how things came to be while also understanding that they are only merely principles. Language will always be broken, misshapen, and irregular, but it’s the exceptions, not the rules, that make it so interesting (this is why I don’t give a fuck about conlangs, by the way).

It’s mildly useful to know about the concept of phono-semantic compounds, because you can still sometimes guess at a kanji’s meaning using components on the left (or the bottom, etc). But you still have to learn the damn kanji.

However, this somewhat eased my mind about the mnemonics method. If, originally, these characters were meant to indicate a meaning and a reading, and if the reading is now lost and can no longer help us disambiguate that meaning, then it’s not so crazy to come up with a story to connect the components together in a way that makes the meaning stick. It’s not my fault that I have to take a shortcut through the world of platonic forms, it’s kanji’s fault! And anyway, this stuff will all melt into the network of my unconscious mind at some point, so I guess it doesn’t really matter in the end.

Ain’t no fun if onyomi don’t get some

I will say, one upside of learning all this stuff about kanji is it made me care a bit more about onyomi and kunyomi in a way I didn’t before. I don’t think it’s worth drilling them, let alone trying to remember which kinds of readings are which, but it can help strengthen one’s intuition for sight-reading new vocabulary.

In English, there’s an interesting phenomenon where the “common” and often irregular words are often from Germanic rather than Latin in origin, such chicken (related to kuiken in Dutch) versus poultry (poulet in French). I’ve heard some explanation about how this is a result of William the Conqueror invading Britain a thousand years ago, but I’m not sure how true that is. As a result, about 60% of the language (I’m making these numbers up) by weight, including the common and irregular words, are Germanic, and you have to learn those the hard way. But for more complex or “fancier” words, like in legal, scientific, or medical contexts, you can often rely on knowledge of Latin or Greek roots to guess the meaning of unknown words or even coin new words altogether.

I think there’s a similar phenomenon going on with Japanese. My intuition is that kun-yomi words tend to be from indigenous Japanese, and they’re usually the words you see when a kanji is on its own in a noun or verb. In words with multiple kanji, instead, you often see on-yomi readings. So even if I don’t think it’s worth learning the readings, I think it may be useful to try to pick up on the kinds of readings I see in these longer or “fancier” words and use that intuition to guess at future ones.

I mentioned medical words before, and I think that’s a great example. I recently encountered 心房細動, which means atrial fibrilation. You may not even know what means in English, unless you know a bit about Latin which clears it up brilliantly. An atrium is a chamber, and fibrillation comes from fiber, like the quiver of a bow — so this means, roughly, the quivering of the heart. If you have a large vocabulary in English and an intuition for this sort of thing, you can transfer that knowledge to romance languages in a medical context:

- French: fibrillation atriale

- Spanish: fibrilación auricular

- Italian: fibrillazione atriale

But returning to the case of Japanese, we can piece together the meaning from the kanji:

- 心 = heart, usually shin in on-yomi

- 房 = chamber, as in 厨房 (kitchen) or 工房 (workshop) — in both cases the reading is bou. The semantic component is 戶, or door, not so far from chamber (in the original Latin, atrium even specifically means an entrance hall!)

- 細 = slight (or thin), as in 繊細 (delicate), which is read sai. And it’s not hard to imagine a mnemonic that connects slight to the semantic component of 糸 for thread.

- 動 = movement (or vibration, in my experience). In compounds, dou.

Slight movement (quivering) in the chamber of the heart (atrium). Nice! Unfortunately, of the kanji here none of them are phono-semantic compounds in a way that is useful to us anymore. The component on the right of 細 might read ta or da, and 房 has the phonetic component 方 which is read as hou and not bou. They’re both fairly common kanji, though, so it’s not so bad.

There are rare cases where compound words are read with kunyomi readings, but there are few of them. The example I was thinking about the other day was 蜘蛛, or spider. Both characters use the component 虫 on the left (where the meaning usually is, remember), and that component means bug. So far, so good. But the components on the right are 知 (to know / zhī) and 朱 (vermillion / zhū), correctly giving us the pronunciation zhīzhū (I don’t know Chinese, so I’m using Pinyin, sue me). In Japanese, the common onyomi (Chinese origin) readings for these kanji are similar; you could read 知 = shi and 朱 = shu, if you really wanted to. We're actually pretty damn close, this is an instance where phono-semantic compounds would have gotten us all the way to the finish line, except…

The reading is kumo, the indigenous Japanese pronunciation. But that’s okay! Spider is a word you only learn once per language, and you might as well enjoy it.